One Move at a Time

Dec. 9, 2020

Creating a cure for a chronic disease is a marathon, not a sprint. In this case, Professor Pam Van Ry and her research team are the race-runners.

BYU weeks begin with hundreds of students making their way through campus — hiking the stairs up from 800 North to the university on their way to class, to work, to the library, and to the laboratory. In the Chemistry Department, students stand for hours, poring over microscopes and flasks. Department professors stand at the fore of lecture halls, gesturing round the room, waving laser pointers, and reaching up to write on whiteboards and blackboards. Many take these everyday actions for granted; however, for those afflicted with muscular dystrophy, a disease where muscles degenerate with use, such actions are difficult and sometimes impossible.

Thus are the Chemistry Department’s Van Ry research group motivated in their research. Professor Van Ry and a team of her students are currently seeking a novel treatment for limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD2B), a variant of muscular dystrophy.

Muscular dystrophy affects 1 in about 7,000 people according to US statistics. Its variant LGMD2B particularly affects the shoulders and hips and afflicts fewer people, about 1 in 14,000 — a statistic that sounds small without context, but unfortunately comprises a somewhat significant part of the population. People of all ages, genders, and races may be afflicted, although symptoms most often develop in childhood.

Muscles normally break down during exercise, then rebuild stronger and larger, explained Van Ry. “But in muscular dystrophy they don’t repair properly,” she said. “Because they don’t repair, some proteins are ‘up-regulated’ [increase in quantity] to make up for the muscles that are no longer there. Galectin-1 is one of the proteins that is naturally up-regulated in muscular dystrophy. Our thought was that by further increasing the concentration of galectin-1 we could alleviate some of the manifestations of the disease.”

Galectin-1 protein contains what is called a carbohydrate recognition domain, meaning galectin-1 can bond easily with glycosylated proteins and, in this case, facilitate the cellular healing process by bonding with broken muscle proteins and helping membranes remain intact. Van Ry’s research team discovered that galectin-1 may be a viable treatment for muscular dystrophy when delivered in small doses that supplement the body’s normal supply. The team’s research method treats extracted muscle cells of mice afflicted with LGMD2B. Such research provides the basis for translational medicine — that is, medicine for one species that may be applied (with some alterations) to medicine for humans.

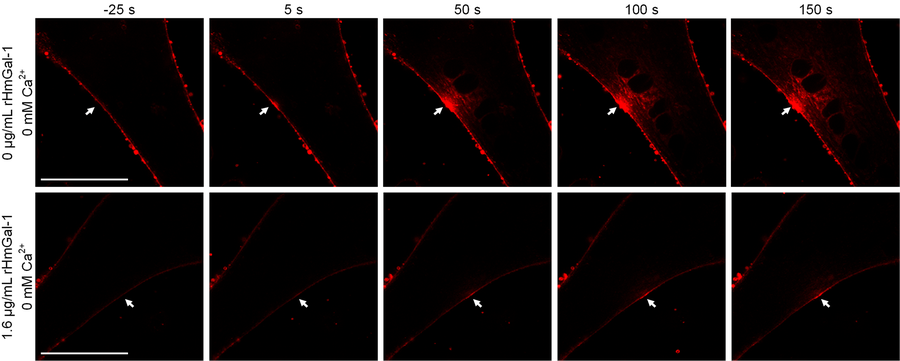

The group did not begin by treating whole mice nor humans, only mouse cells or muscle fibers afflicted by LGMD2B. Recent team research displays promising results in injured cells and fibers treated with galectin-1.

“We were super, super stoked,” said Van Ry. “We’ve [showed] that it decreases the disease and it can do so very, very quickly, within 10 minutes, which is really crazy. We were very surprised.”

Pictured in the above photos is a dyed mouse cell afflicted with muscular dystrophy (left) and a time progression of galectin-1's movement in mouse cells after 10-minute and 48-hour treatments (right). These photos were submitted by BYU graduate student Mary Vallecillo-Zúniga.

After experimenting with multiple dosage volumes and frequencies, the team discovered that mouse cells receiving doses of 2.7 milligrams per week of galectin-1 healed muscle damage significantly.

Galectin-1 treats more muscular dystrophy symptoms than just muscular degeneration. Part of the research group’s work has focused on galectin-1’s effect on the immune system.

The immune system operates unusually in patients with muscular dystrophy. Healthy immune responses disappear after their trigger disappears, like the body stops scabbing after a cut heals over. But in people with muscular dystrophy, the immune response rises to such an abnormally high level that another immune response is released to counter the first.

“I call it the Goldilocks effect,” said Van Ry. “You have an initial immune response and then you have another immune response that counteracts [the first]. It’s always this balancing act going on inside of you… in muscular dystrophy their system [stays] in a hyperactive immune response.”

Such an immune response exhausts and weakens the body. Galectin-1 can modulate some of these responses — treating another symptom of muscular dystrophy — while acting as a “glue” (as Van Ry calls it) for the outer membranes of muscle fibers.

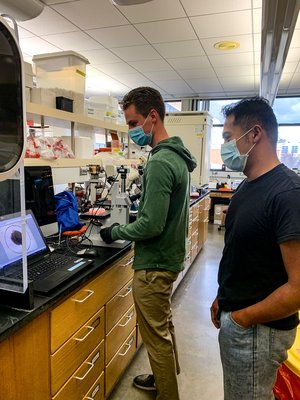

Pictured in the above photos are Professor Pam Van Ry (left) inspecting frozen mouse muscle cells and undergraduate Dallin Jacobs and graduate student Jonard Valdoz (left) analyzing a cell culture.

In addition to lab work, Van Ry’s team visited conferences and collaborated with other researchers in pursuit of success.

“It has been a rewarding process… [learning from] other teams and individuals working together towards a common goal of improving… the well-being of individuals suffering from such a debilitating disease,” said Mary Vallecillo-Zúniga, one of Van Ry’s graduate researchers.

Vallecillo-Zúniga currently seeks a PhD degree in biochemistry. In Van Ry’s lab, Vallecillo-Zúniga designs and performs various experiments and analyzes and presents findings to the team and other researchers. She and her fellow graduate students Ashley Markham, Jonard Valdoz, and Matthew Rathgeber help Van Ry train and supervise the research team’s seven undergraduate students. Also a part of the team are Emory scholar Dr. Connie Arthur and Harvard scholar Dr. Sean Stowell, who is a BYU alumnus.

The Jain Foundation sponsors the Van Ry group’s work.

“We were super fortunate to get in contact with them,” said Van Ry. “They only fund people working with [LGMD2B]. They have a team of researchers and patient advocates that determine whether your research is funded or not. They hope to come together and provide some sort of treatment option to help these patients, because at this point the only treatment these [muscular dystrophy patients] have is palliative care, which just tries to minimize their symptoms… doesn’t really cure them.”

While the Jain Foundation sponsors Van Ry’s current research, her interest in muscular dystrophy is rooted in her education.

As a graduate student at the University of Nevada-Reno’s Pharmacology department, she was tasked with unlocking the capabilities of a particularly tricky protein. Professors and students at the university had hypothesized that the protein could possibly treat muscular dystrophy symptoms, but no one proved this until Van Ry was recruited to the work. The protein she unlocked was galectin-1.

After graduating, Van Ry stayed at the University of Nevada-Reno as a postdoctoral fellow, in which time she received funding to continue researching galectin-1 and muscular dystrophy. Once her immediate projects on the subject were complete Van Ry began to explore other areas of research and temporarily put muscular dystrophy aside. However, she continued to believe that crucial discoveries remained concerning galectin-1, and so she returned to the research as a BYU professor with students of her own.

“I always felt really strongly that there was an immune component that we never found,” Van Ry explained, referring to galectin-1’s role in treating hyperactive or chronic immune responses.

The Van Ry group continues to study the treatment of muscular dystrophy in mice. In the future, the group hopes to test galectin-1 therapy on other, larger animals before progressing to human trials.

“A [cure] is quite a ways out… minimally… ten to fifteen years. It takes quite a while,” lamented Van Ry. “My hope is that by working with the Jain Foundation they can speed [our work] because they have so many [experts] affiliated in the field of muscular dystrophy.”

“We have a lot more work… to be done. It’s an amazing start,” said Van Ry.

“I love being a part of the muscular dystrophy team,” commented Vallecillo-Zúniga. “This project has given me an opportunity to serve and give hope to people suffering from [muscular dystrophy].”

The Van Ry muscular dystrophy team published a paper in biochemistry journal PLOS One entitled “Galectin-1: A Potential Protein Therapy for Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophy 2B” describing their research and conclusions in detail. The paper may be read here.

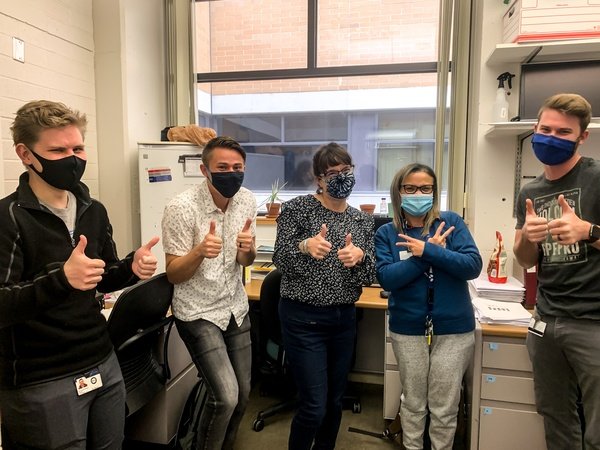

The photo at the head of the article portrays several members of the Van Ry muscular dystrophy research team. From left to right are undergraduates Danial Poulson and Christian Arnold, Professor Pam Van Ry, and graduate students Mary Vallecillo-Zúniga and Matthew Rathgeber.

BYU Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry reporter Sydney Jezik wrote this article and took all uncredited photos above.